Tractors, milking machines and mechanized combine harvesters–innovative technologies that transformed small-scale farming into large-scale agribusinesses. Now we are on the cusp of another technological revolution, this time one that will both increase efficiency and reduce the environmental impacts of food production.

Until the autumn of 2021, Finngarne farm in the environs of Norrtälje was like any other Swedish dairy farm. But the owner Jörgen Eriksson has always been interested in new technology and is a long-time member of Arla, so when the farmer-owned dairy cooperative asked him if he wanted to become a Swedish innovation farm he didn’t hesitate.

Innovation is needed if we are to achieve the climate goals that Sweden has set for 2045 and to ensure that the technology runs smoothly everything must be tested and evaluated on a real farm. This is what we have in mind to do here, declares Åse Arnbratt, senior manager at Arla Foods.

The idea was suggested by Arla’s operations in the UK, and in October 2021 the Swedish innovation farm was inaugurated.

Cows on Finngarne farm

– In the past, it has been difficult for both researchers and technology companies in the agricultural sector to verify projects, but this farm lets us carry out tests in the real world, says Åse Arnbratt.

For example, next year the Finngarne farm together with IVL Swedish Environmental Institute plans to investigate how eDNA technology can be used to identify biological diversity, and there are also several projects underway to evaluate new technologies that can bolster animal health.

But the important win for Arla is that knowledge generated at the innovation farm spills over into commercial agriculture rather than being locked away in research reports.

– That is why we welcome visitors to the farm so that both our members, researchers and companies can come here and see what we are doing and in this way, the knowledge we have gained is spread out into the real world. This will enable us to promote sustainability and ramp up agricultural efficiency – two benefits that often go hand in hand.

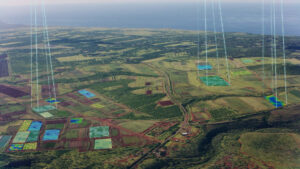

The Vultus Agtech company, headquartered in Lund, slap in the middle of one of Sweden’s most fertile agricultural landscapes, is on the same wavelength. The company helps entrepreneurs pinpoint where and how much to fertilize and irrigate by using satellite images that reveal soil health and nutrient needs.

Vultus’ services are based on satellite and weather data

– Most of our customers utilize an image resolution that divides fields into squares of ten-by-ten metres, but we can zoom in further and see how a specific row of vines is doing compared to one growing 60 centimetres away, says Per Karlsson, CEO at Vultus.

The concept is to provide satellite data that will enable farmers to ascertain the status of the soil in specific locations and make it easier to apply the appropriate measure in that particular spot. Instead of blanket fertilizing the entire field, fertilizer can be applied only where needed. This is beneficial for the farmer’s wallet and helps reduces the risk of eutrophication.

–Soil can only absorb a limited amount of nutrients, and any surplus fertilizer will be leached out – at best this will help the neighbouring farm, at worst it will trigger harmful eutrophication in lakes. rivers and the Baltic Sea.

In general terms, the technology provided by Vultus can help farmers reduce water and fertilizer consumption by almost 20 per cent. This is important as groundwater levels fall and fertilizer becomes more expensive. But the technology can also be used to analyze soil nutrient content over time, leverage harvest planning or calculate soil carbon content. And Vultus is far from alone in predicting an increase in the use of agricultural technology in the years to come.

During the period 2018 to 2021, the research institute RISE, therefore, launched a digitalized agriculture testbed to evaluate how new technology can be used to increase sustainability and profitability while reducing agriculture’s fossil footprint.

– One of agriculture’s great benefits is that it enables the soil to store carbon, however, there are big challenges from fossil emissions from fuel and plant nutrients, says Jonas Engström, operations manager at the RISE testbed.

Jonas Engström, RISE

– We wanted to build an innovation environment that supports agricultural digitalization, automation and electrification and that can help solve these challenges. During the three years the project has been running, RISE, together with eighteen other participant organizations, has constructed an innovation environment at Ultuna, near Uppsala. Here they have tested autonomous electric machines, both third party and those custom designed on-site.

– Currently, there are perhaps about twenty autonomous field machines in commercial use in Sweden, but we estimate that they will in all probability play a major role in the future. In organic farming where weeds cannot be controlled using chemical agents, they quickly become

profitable. Autonomous machines could also reduce the size rationalization that leads to the exclusion of smaller farms.

– During the 20th century, agricultural productivity has increased, due among other things to bigger machines, which means that a single worker can be more effective hourly.

In the 1950s a new tractor weighed around 1.5 tonnes, today a new tractor today may well weigh as much as 20 tonnes. This has acerbated harmful soil compaction and small farms find it difficult to match the lower costs the new machines are able to deliver.

– But autonomous machines can conceivably counter this trend, several small machines are able to carry out the same amount of work as one massive one, leveraging access to new technology regardless of the size of the farm.

However, there is some inertia in the transition to new, environmentally smart technology.

– Agriculture is an industry with low margins and technology must both work and be profitable if a breakthrough is to be achieved. In the agricultural sector automation, digitalization and electrification are still in their infancy, and it will take a lot of work going forward to introduce these on a broad front.

Text: Karin Aase